Two’s Are Now Underestimated – The Mikan Drill For Stocks

George Mikan was the very first superstar of the NBA. He was the key to the league even surviving before it could thrive. Making him one of the most underappreciated athletes of all-time. Maybe because he was not athletic at all. His go-to move can best explain how to shoot a high percentage in the Stock Market as well, always has, but it has become equally under-utilized.

So, let’s dust off some old clips and head to the film room. I will even step out just a bit from his sweet spot, and share a long range belief that both leagues of deep shots and stocks are now overrun with analytics and perfectly set up to be revolutionized once again – with informed simplicity. If you are looking for simplicity as a stock trader there are platforms similar to Stocktrades where you can subscribe to have access to information to make smarter investing decisions.

In both the NBA and Stock Market, I think the old fashioned TwoPointers are now wonderfully un-crowded.

Stick with me for this beautifully boring, with no room for algorithms, idea I had while comparing almost 80 years of shot and stock charts next to each other. In doing so, I even confronted my own severe bias towards analytics. My college athlete interns giggle and call me a high level mathlete for a reason. I have openly praised Daryl Morey before most knew who he was. But like all brilliant ideas in the world of capitalism, they attract a crowd. I hate crowds. So, I wondered if there was a spot on the court and Stock Market with a little more elbow room.

In August 1949 the NBA was born. A merger between the small towns in the National Basketball League and big cities from the Basketball Association of America was agreed upon at the Empire State Building in New York. Seventeen teams made up the new NBA. But, the league was in trouble from the start. Fan support kept shrinking and in a few years they were down to only 8 teams with bankruptcies and empty arenas all over.

Still scarred by the Great Depression, a generation of investors stayed away from the Stock Market at this time. It took until 1954 for the Dow Jones to recover back to its previous peak in 1929. Long periods of going absolutely nowhere are much more common in Stock Market history than most bulls or bears recognize. Not good for business for either camp I suppose.

“New high” makes a better headline than “back to where it was a few decades ago.” But they can both mean the exact same number. A distrust for banks and Wall Street led to the Glass Steagall Act after the Stock Market crashed. A very small number of Americans were common stock shareholders at this time.

Sounds familiar.

When I was a kid, the very first basketball shot you ever learned was called the Mikan drill. I never heard the part when George was cut from his high school basketball team.

Openly described as too awkward, the coach told him, “You just can’t play basketball with glasses on, you better turn in your uniform.” George wanted to keep playing so he went to the YMCA where he promptly broke his leg so badly after stepping on a ball, that he could not walk for a year. Hobbled, George decided to become a priest instead. He enrolled at Chicago’s Quigley Prep Seminary as a sophomore and gave up on basketball.

This is the guy that saved the NBA? Let us all keep this part in mind next time we think saving a little more for retirement sounds daunting.

Priesthood did not work out either. Now enrolled in college and unable to tell his family about changing direction, his father only learned that he must have picked up a basketball again when he read in the newspaper about a “…Mikan kid on DePaul’s team.” Coach Ray Meyer invested time in his footwork to combat how awkward he was. He told George to even work at it during school dances by finding the shortest girls. George recalled, “He figured that would force me to improve my footwork, otherwise I’d step on them and hurt them.”

George tweaked one of Meyer’s drills and developed his own simple routine. He took the ball directly under the basket and with one step learned how to lay it in with his right hand, jumping off his left foot. Catch it from the net with both hands. Then, one step to lay it in with the left hand, jumping off the right foot. Over and over, both the hands and feet learning the basic recipes for scoring anywhere close to the basket from any angle. George made three hundred of these 2-foot baskets per session. The Mikan Drill was born.

All of those two-pointers from point blank range led DePaul to the national championship. George set a Madison Square Garden record with 53 points in the semi-final game.

The year the NBA was born the Minneapolis Lakers took Mikan and won the championship. To try and help take away Mikan’s short 2’s the league widened the lane from six to twelve feet, known as the “Mikan Rule.” The league even tried using 12-foot baskets to slow down Mikan’s signature shots close in. It backfired. The outside shooters were the ones who suffered the most. That experiment was scrapped after one game.

The most extreme example of trying to stop Mikan occurred on November 22, 1950 when the Fort Wayne Pistons decided to keep it out of Mikan’s hands. When the Pistons had the ball they just held it. During the game fans were reading newspapers in the stands or walking out. The NBA reached its absolute low with a final score of 19-18. Continuing to carve up the middle, Mikan won five championships from 1949 to 1954.

Thanks to George Mikan, the 24-second shot clock was born in 1954 and saved the league. What we now take for granted as moving the fastest sport along with marvelous tempo, started out with one volunteer near the court holding a stopwatch and yelling “Time!” after 24 seconds elapsed. By the end of the season, however, all teams had clocks installed around the courts, visible to all and the NBA survived as a result.

George explained, “Back in those days, I’d arrive by train or plane a day or two ahead of the team to promote the game.” George described sitting in the lobby of the hotel “To try to drum up business and sell tickets. I never minded any of the extra obligations. You know, when you think about it, it was pretty good stuff for the big kid with the glasses who nobody thought would be able to play.”

You might wonder how you could you possibly mess up the Mikan drill, whether a die-hard hoop fan or reading about that simple idea for the first time.

Go into any gym and you will see the exact opposite being practiced today, thanks to the analytics boom from the NBA. You will see high schoolers wide open, with the ball in their hands in front of the rim unguarded, exactly where the Mikan drill begins. Only now, he is instructed to lean around under the backboard and rifle a one-handed pass 23-feet to the corner so the shooter can take one step…into a 3pointer instead.

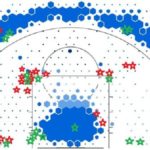

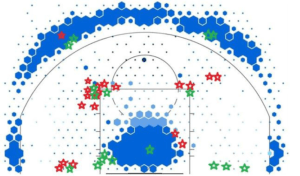

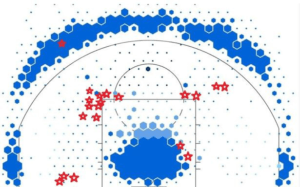

Spatial analytics technology from MIT, originally designed for the Israeli Army for missile tracking, is now in the ceiling of every NBA arena. Analytics says 3’s are more valuable than 2’s. In 2010 only four teams had this technology. By 2013, every team had it installed. Years before other teams installed the technology, and well before they analyzed it, Daryl Morey was changing the way basketball would be played in Houston. Here is where every shot was launched by his Rockets last year.

No longer were players looking for good open shots, or even their favorite shots, as the first century of basketball instincts had taught them. Now, they were pre-programmed for what the computers said were the most efficient shots. Kevin O’Connor wrote, “An LED board wraps around the Rockets locker room, above each player’s stall. But it doesn’t flash motivational quotes from Vince Lombardi or Jack Ramsay; it shows stats: offensive rating, defensive rating, effective field goal percentage, and quality-shot percentage. You get the feeling you’re in a mad scientist’s lab?—?a stat geek’s man cave, not a sweaty locker room for alpha males.”

The mad scientists wanted as many 3’s as possible now and the most precious element isolated in that lab is called the “short corner.” You see, in the far corner of the 3-point arc, by the baseline, it is exactly one foot closer to the rim. Untold billions of dollars began chasing that one foot when you add up all the contracts being given to 3-point specialists, staffs organizing offenses around them, and the technology departments being built from scratch to analyze this data. Then add in all the younger institutions aspiring to the NBA and you have a full blown revolution.

When plugged-in sports sites like the Biglead.com start running articles in 2017 titled: “Houston Rockets Have Nearly Perfected Basketball” I will make a very solid guess that Morey has already begun analyzing something much more un-crowded and far humbler than that notion. Leslie Alexander, the Rockets owner, just sold the team. I’d note he made his original fortune as a trader on Wall Street. Maybe completely unrelated facts, but he knows what a top tick means.

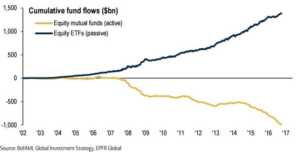

All that money and time and effort to find that one foot of difference sounds familiar in the Stock Market. It is no accident that some of the best quants on Wall Street are now leading sports franchises. Indexing with ETF’s have revolutionized their game as well. Unquestionably more efficient systems have taken over each sport.

I have no dog in either of those two hunts, I do not own ETF’s or Mutual Funds. I think more efficient systems like Morey’s and Indexes win for very clear reasons – better math.

But, the smartest ideas attract crowds. The very origin of the sports analytical movement was written about by an ex-Wall Street guy and fantastic storyteller, Michael Lewis in Moneyball. The un-crowded key was not just better data but specifically finding the better data that was under-analyzed by others. No investing book does a better job, in my mind, highlighting the advantage of un-crowded analysis. It has been reported that when Lewis spoke to John Henry, owner of the Boston Red Sox, he offered to pay Lewis NOT to publish the book. Seasoned from a remarkable career trading futures contracts on Wall Street, John Henry knew better than most that once inefficiencies in quantitative analysis are discovered, your edge erodes. In economic circles it is called the Goodhart principle, which states that when a measure becomes the target it ceases to be a good measure.

Bridging sports and investing again recently, Michael Lewis discussed active and passive investing. “There was a shift away from the intuitive judgment of experts. The move of active management inflows to passive management is one of the great changes that has swept the investor world since I stepped foot in the business. In the extreme no one is making judgments.” Liar’s Poker, The Big Short, and Flash Boys are among his portfolio of remarkable books of Wall Street extremes.

I think short-corner 3’s and indexing are wonderfully efficient locations, let me be clear. They are historically efficient solutions that completely changed each marketplace. But, I think the two-pointer is now underestimated in both shots and stocks.

To me, the Mikan drill in the Stock Market is ownership of a good oldfashioned common share of stock to collect a dividend. Over and over, with right and left hands. Taking your shots from lower-risk locations is easy. What’s hard is ignoring the crowds gathering at higher payoffs around the 3-point arc of other investment possibilities.

Only what is made real in the form of a dividend, in your hands as a shareholder, is what I call your Mailbox Math. The peace of mind that arrives from zero concern about shooting for any alpha while walking to the mailbox to collect those dividends, others have called their championship of ‘aha’ moments. Zero stock price appreciation is factored in, planned for, or worried about, at all.

One of the great things about this Mikan drill in the Stock Market is you do not have to be very innovative to focus on Mailbox Math. By definition, you do not step outside for deep shots. You can miss all the explosive opportunities that most investors dream of.

Let me give you an example. It was 1996, and the Chicago Bulls were about to win their second of three straight championships. Your humble mathlete here was building retirement plans at a large Wall Street brokerage firm.

My car eased over the giant crack in the driveway from a tree root. I walked up to the smallest and oldest house, by far, on the street. The new big homes all around, had very few trees left to worry about any deep roots. Inside, the unfashionably low ceilings brought sounds from the stereo and smell from the coffee pot a bit closer. Nobody described the scene any better than Thomas Stanley when he wrote, “We began studying how people became wealthy. Initially, we did it just as you might imagine, by surveying people in so-called upscale neighborhoods across the country. In time, we discovered something odd. Many people who live in expensive homes and drive luxury cars do not actually have much wealth. That small insight changed our lives.” – The Millionaire Next Door.

My host greeted me with a hug and walked me into the living room where meticulously laid out, end to end, were rare artifacts called common stock certificates. Yellowing from decades gone by and their corners turning up, we did not touch them. We just sat and visited. There was a great story attached to each, and I was in Stock Market heaven just listening. The brokerage firm expected me to conclude the meeting by carefully grabbing those shares like Indiana Jones in Raiders of the Lost Ark, and in one motion quickly replace that pure gold with a bag of sand from some Wall Street manufactured product.

We chose to do absolutely nothing instead. Over the past twenty-one years we visited, exchanged jazz CD’s, and became close friends. They never stopped walking down that same sidewalk, also cracked by another tree root, straight to the mailbox to collect their dividends. Their four biggest Mailbox Math positions were Chevron, Coke, 3M, and WalMart. Not caring one bit about price action, or the overall market, and never fixing the sidewalk, they got to focus on WHY to be retired. (I’m no scientist, but with a large focus group I’d note: giant smiles and longevity seem to be associated with good Mailbox Math.) We simply believe that certain companies are able to create their own economies with enough cash flow to pay dividends without interruption.

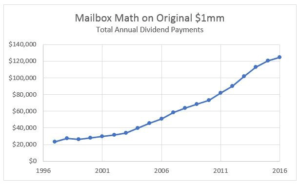

Equal portions of an original $1 million held in common shares of those four companies paid annual dividends that reached $124,527 in 2016 and it has risen again in 2017. There were plenty of higher yielding stocks in 1996 just as there are today. At the beginning of this chart those four combined for an annual yield of only 2%. Lots and lots of Two-Pointers add up.

Mailbox Math assumes zero growth from individual price change and zero overall market appreciation. Those four yellowed certificates continued to pay dividends after we safely deposited them at the large brokerage firm where I began my career. Like George Mikan, I had been called awkward before. So it was not hard to ignore all…ahem … requests by management to pitch different products. The trust I had forged on a recommendation to do absolutely nothing would be monitored based on income progress reports, not re-allocations. We tracked carefully their Mailbox Math, straight through two different 50% market crashes over those two decades. We watched the dividend streams continue uninterrupted with increases of more than 9% on average, each and every year. These sweet common stock shareholders never asked me what smart beta was. It was just one step off the left foot…catch…one step off the right foot….catch….straight to the mailbox.

Today, I fear that a generation of investors thinks this story is an old relic like the Mikan drill and will not work again in their lifetime. We have decade’s low ownership among U.S. households of the Stock Market through any vehicle, down more than 20% over the past ten years to only about half of Americans now according to Gallup Poll data.

But the real story to me, is that just a tiny fraction of a fraction of those are actually common stock shareholders patiently holding any one of them for decades in their own account, rather than inside any other vehicle. The crowds have gathered around better analytics.

So, does the Mikan drill or Mailbox Math have any place in today’s NBA or NYSE?

I took that new age basketball shot chart above and went back to some old school films to overlay a nagging theory I had. My core memories are full of watching game-winning shots, when location mattered most, occurring at only a few different spots on the floor. Today’s analytics hate those spots.

One, in particular, had always stood out to me in a very non-analytical and simple way – the elbow – which is the corner of the paint, on the edge of the free throw line. If you are attacking the basket and your defender is retreating, you can stop and pull up for a midrange jumper before the defender retreating can recover. It’s why players of any size can get their shot off right there without it being blocked. The same is typically true from that distance from anywhere on the court attacking the rim. This is the blank space in that shot chart above, where shooters are told to NEVER shoot from now. But, when it matters most, and all the analytics and systems in the world just need one game-winning shot – where do they come from? Well, the guys with the deepest bank of game-winning data to pull from are named Michael Jordan and Larry Bird.

Among the most famous Jordan game-winners was this 1989 fist pumping close-out classic in Cleveland.

I remembered that shot from the elbow very well, and a few more. I had to go find all the others. I put a red star on top of the Rockets’ shot chart everywhere Jordan hit a game-winner. Fourteen of the twenty came from the elbow!

Jordan liked finding sweet spots just like the quants in the analytics departments. But, his were always closer-in and have won more a lot more titles. You can say he’s an outlier. He could jump over people. That’s exactly why he should have been biased against developing a mid-range shot. He did it because it was the most un-crowded spot on the floor.

So, let’s look at a different guy then who could barely jump over a phone book. I was prepared for my theory to be challenged severely by The Legend. Larry Bird was the original 3-point marksman. He won the first two all-star weekend 3-point contests in the late 1980s and walked in the locker room for the three-peat to ask before it started, “So, who’s playing for second place?” He won that one also.

The man was so cool, he never even took off his warm-up jacket. Notice something else, he won it from the short corner, where he was deadly. But when it mattered most and he had to play against defense, the most clutch 3-point shooter the league had ever seen throws a wrench right through today’s analytics and took the 2’s instead.

I added green stars to our shot chart to show Bird’s game-winners. Almost every single one of these game-winners are made where all of today’s players are told are the worst places to shoot from.

Now, go back and look at poor Craig Ehlo spinning off the court to his knees in disbelief in one of the NBA’s iconic highlights. What I had forgotten until watching the whole tape again was Ehlo had just made what could have been the game-winner himself! He left just three seconds on the clock before Jordan’s dagger. Ehlo, a former beloved benchwarmer for the Rockets, was inbounding the ball from half-court to any of 4 all-stars on that Cavs team. Hall of Famer Lenny Wilkins had drawn up a vintage give-and-go, right back to Ehlo without the use of one dribble. He made a 2-pointer off the glass exactly where Mikan started his drill. All of this occurred in the last 6 seconds of the game. Because just before that, Jordan had silenced the crowd with what could have been the original of three potential game-winners from….you guessed it, just inside the elbow. He took the two, again.

Take those seven seconds of beautifully orchestrated basketball for high percentage shots from the most talented player to one of the least, and contrast them with how games end over the past several years. Have we

gotten too analytical for our own good? Now, when it matters most at the end, computers freeze up and crowded spots force awful decisions. Are we talking about shots or stocks?

An entire generation of high school and college basketball players have all grown up learning about more efficient shots and can show you exactly where the short-corner is. Just one small problem. It is not any shorter for them. What??? Nope. I even talked to coaches who had not stopped to actually do their own math. Only the NBA 3-point line is shorter in the corner. For the other 99%+ of the players at every other level it’s exactly the same all the way around the arc. Deep analytics and crowds around them start overlooking the simplest math.

I think the Two’s are awfully un-crowded.

In the Stock Market you do not have to go back in time or wish you could have been like any millionaire next door example during the good ole days. You can easily get 2% dividend yield right now, just like they started with. If you look for companies who have never interrupted payments and increased them every single year during those past two decades or more – affectionately called the Dividend Aristocrats – you would be starting with a 2.5% dividend yield. Despite any number of extremely analytical reasons to try something new along the way, those dividend payments have been increasing more than 9% a year.

So, if you get a Stock Market with explosive growth…or one that crashes 50% twice…or one that might go absolutely nowhere much longer than most like to consider, then you could practice the Mikan drill for stocks instead and focus just on the Mailbox Math.

You are looking at dividend paying stocks averaging 2.5% yield, with payments increasing at 9% per year, and re-invested quarterly. In ten years you have more than three times the yield on your original cost basis. You could then choose to receive payments in your mailbox instead, and enjoy living off that income.

I don’t care how efficient new systems are. Some things are so beautifully simple they do not need improving. They can hide in plain sight and never attract a crowd. The Mikan drill still works for both shots and stocks. I think the simple Two-Pointers may now be underestimated.

www.kc-roi.com

Twitter @RyanKruegerROI

Category: Blog